This tall elegant Charioteer of Mozia or "Giovane of Mozia," was excavated in

1979. It brings up problems of identity, meaning and dating in Greek Art.

A life-size statue was dug up in 1979 in Mozia, ancient Motya, a tiny island adjacent to the west coast of Sicily. The slightly larger than life-size Youth of Mozia demonstrates why it is necessary for art historians to constantly re-evaluate conceptions of style, meaning and dating in art. Everyone agrees it belongs to the 5th century BCE, and, based on exact location of the find and the layer in which it was buried, it cannot be later 397 BCE. Yet Mozia was a Carthaginian settlement and the Carthaginians were constantly at war with Greeks who controlled most of Sicily.

The questions are:

* Who is the subject?

* What is the date?

* Where was it made?

* Why did it end up in Mozia?

This statue has physical beauty, elegance, grace and transparent drapery. Feet and arms are missing but remnants of one hand dig into the corresponding hip, a marvelous detail which only an artist of great skill could execute. Much of the face is damaged, perhaps intentionally. The head was detached but has been put back. Although Most experts agree that the statue is Greek dating to the 5th century BCE, some have claimed the hair and face appear non-Greek and perhaps Carthaginian.

Bent arms in opposite directions would have created a vigorous counterpoise, a surprise

considering the rigidity of some conventional aspects of the head and hair.

The pose, vigorous turn and thin, transparent drapery would suggest a classical date of 450-420 BCE. "Wet drapery" is

mainly a convention of female figures of this High Classical period or end of the 5th century BCE, as in the Parthenon goddesses or on the Temple of Athena Nike. Yet there are contraindications to a late 5th century date. Hair is very stylized, and therefore, Archaic, and the facial modeling is most akin to the Severe Style, 480-450 BCE. To get better idea of a date, we can compare to other Greek sculptures, and I will fill in a suggested idea of identity.

When I compare this beautifully carved wet drapery to other works, the strongest analogy is found to the Ludovisi Throne, probably representing the birth of Aphrodite. This relief, dated c. 460 BCE, is now in Rome, but is known to have been connected to an Ionian temple of Aphrodite in Locri, a far southern city in Italy. (Both Sicily and southern section of Italy were heavily Greek in the centuries before the Roman conquest.)

The Ludovisi Throne, usually dated to 460 BCE, comes from a Greek colony is

south Italy. It has similar "wet drapery."

When I look at the profile, I'm reminded of the Kritios Boy, c. 480 BCE,

also in marble, although the Kritios Boy had inlaid eyes of another

material. Short stylized

hair held down on the scalp are characteristic of both statues. The Mozia youth's capped hair ends in ringlets, an atypical feature, but not without parallels. It's unfortunate the center of this figure's nose, mouth and chin are no longer visible in their original form for a perfect comparison.

The profile of the Mozia marble reveals holes in the ear and even some bronze in the back of the head, perhaps an attachement for the victory wreath of a charioteer.

The Kritios Boy,below, is in better condition.

His eyes, missing, were inlaid with another, colored material.

The Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, is bronze and has original inlaid eyes.

He is a victorious chariot driver from Sicily but was dedicated in Greece.

The bronze cast Charioteer of Delphi, c. 470 BCE, represented the winner of the Pythian games who came from the city of Gela in Sicily, but the statue was made in Greece and erected to Apollo in thanks for a victory Apollo at the god's sanctuary in Delphi. He has copper inlays for lips and eyelashes, onyx for eyes and silver for the victory wreath, which fortunately remain intact. Yet the Delphi Charioteer, c. 470 BCE, is more rigid than our marble example and his face is mask-like. He was part of a bronze group composition, standing behind 4 horses and such stoic emotion was needed for the concentration of an athletic victor. (Remains of the horses, reins and the statue base with dedication are extant.)

The Mozia figure also wears a ankle-length chiton, the

xystis that all chariot drivers wore, although without sleeves and in a very light fabric. Besides the

xystis, there are other reasons that the Mozia youth can be considered a charioteer. His thick belt of a stiff material compares to the belted chests of charioteers seen on Sicilian coins dated to 460 BCE and later, an alternative to the Delphic Charioteer's belt on the waist and back. Such belts or ties were necessary to keep the fabric from billowing in the wind and interfering during a race. Here we see large holes to which a bronze belt buckle must have been attached. Finally, holes in the head above the row ringlets held bronze nails, two of which remain, evidence of a victory wreath attached to the original statue. The right arm, missing, was probably raised to attach the wreath, while the left arm was bent nonchalantly where the remaining hand reaches below at the hip. T

he statue may be something the charioteer himself erected to honor his victory, and placed it at home in Sicily, rather than in a sanctuary dedication on the mainland of Greece. (These details are explained by Professor Bell, who suggests it was made by a Greek artist for a victorious Sicilian charioteer patron.)

The Kritios Boy, about 480 BCE right, is in the Severe Style.

He is slightly under 4 feet tall.

The statue from Mozia has a stonger

shift to his hips than the Kritios Boy.

The Kritios Boy was excavated with many other statues in the Acropolis of Athens in 1865. It is generally known to mark the transition from Archaic to Early Classical or the Severe Style, as its legs shift position and transfer weight into a counterpoise, the relaxed pose of contrapposto. Severe Style art from 480-450 BCE is known for its stoicism or a lack of facial emotion.

There is a youth from Sicily made around the same time as the Kritios Boy, the Ephebe of Agrigento. If we compare his face with the Mozia figure, we see the similarities, a serious demeanor with broad feat

ures, less elongated than the Kritios Boy or the Charioteer at Delphi. So questions of his "Greekness" should be eliminated.

The Ephebe of Agrigento (ancient Akragas), left, comes

from Sicily and is dated around

the time of the Kritios Boy, above.

Why was the Mozia Charioteer, if made by a Greek for a Greek in the 5th century, found in Mozia? In a constant battle between Greeks and Carthaginians, with the major Greek cities being ravaged between 409 and 405 BCE, this prized statue would have been captured as war booty. If you have any thoughts of date or identity to add to this blog, please comment.

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

In Selinunte, Sicily, the remains of several Greek temples from the 6th- 5th century

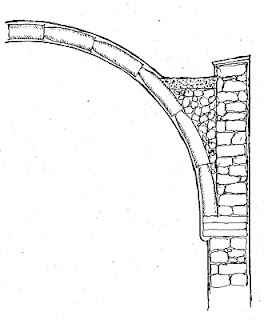

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high.

This temple had columns about 54 feet tall. Here, we see the columns were made of individual segments called drums, each of which are 12 feet high.

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the

Though only a small portion of the peristyle remains, the Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.

Construction began in 480 BCE and was still in progress when it was decimated in 407 BCE. The Telemon or Atlas figures whose bent arms support the architravemay in fact represent Carthaginian prisoners who had been made to build the temple.  But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen,

But even these giants, who appear to have held up the building, have fallen, Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,

Ancient Akragas may have had 200.000 people in the 5th century BCE.Today we witness the fallen giant as a symbol of human pride grown too large,