|

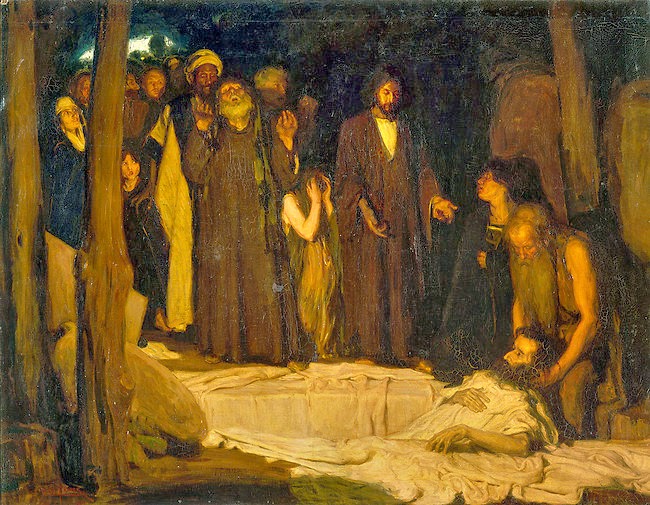

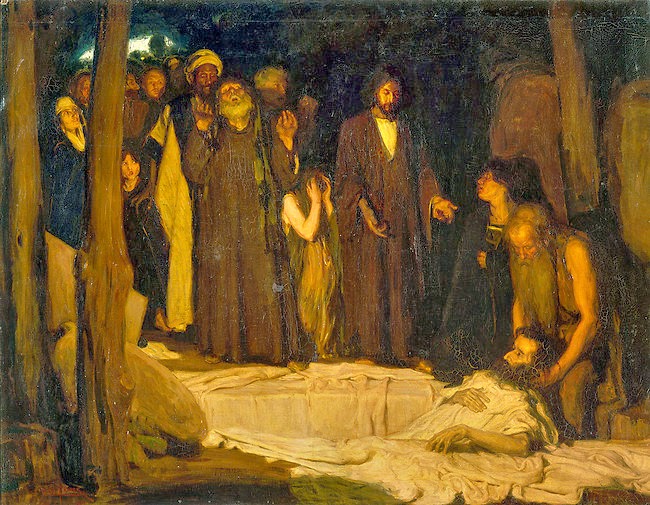

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Raising of Lazarus, Musee d'Orsay, Paris, 1896 |

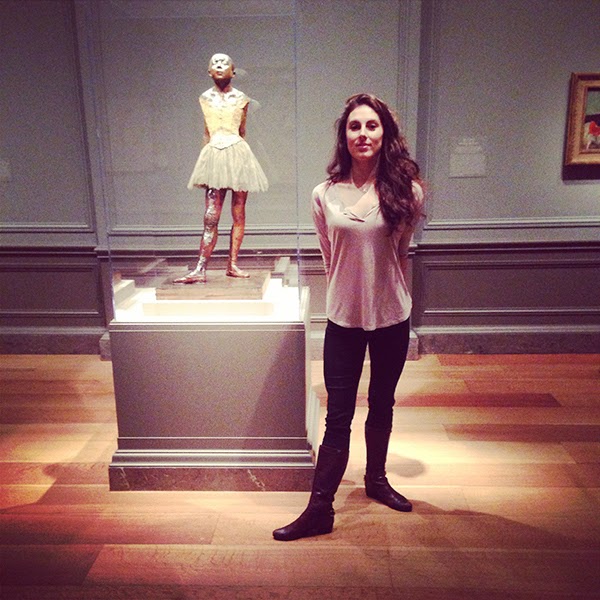

Henry Ossawa Tanner, the most important African-American painter born in the 19th century, should probably be considered America's greatest religious painter, too. He came into the world in when our country was on the brink of

its Civil War, in Pittsburgh, 1859. Though his paintings are profound, he normally doesn't get as much recognition as he deserves.

Religious painting has never been a significant genre in the United States. Mainly, it has been used for book illustration and in churches with stained glass windows. Of course, Europe had its own rich tradition of paintings for Catholic Churches and even in the Protestant Netherlands, Rembrandt made paintings and prints of biblical subjects for their religious significance.

Tanner reinvented religious painting with highly original interpretations. His father was a minister in the AME Church who ultimately became the bishop of Philadelphia in 1888. His mother was born in slavery, but escaped on the underground railway. Although Tanner was born free, he obviously experienced turbulent

times and discrimination; faith could have given him solace.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, 1894, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

In 1894, Tanner painted Mary, mother of Jesus, at the

Annunciation, the biblical story of an angel announcing to Mary she is to be the mother of God. Typical Annunciation scenes put a flying angel interrupting a teenage girl in her bedroom. Tanner leaves out the angel and only a beam of light represents the divine encounter. Pictured as a young women in her bedroom, Mary reflects inward on the meaning of the light, knowing God has things in mind for her. The painting is absolutely beautiful, a show-stopper with a profound imagining of how Christ's earthly life began. The streak of light appears as the leg of the cross as it passes through a horizontal shelf on the wall. When we notice this detail, we're given a hint of how Jesus' life ended, death by crucifixion.

|

| detail-The Raising of Lazarus |

Tanner's technique uses mainly the pictorial language of realism to convey divine presence on Earth, in contrast to

Abbot Handerson Thayer

who used symbolic angels and winged figures in an idealized classical

figural style. Another way to explain the difference is to say that

Tanner painted in a vernacular language, instead of using the classical

Latin language. His religious stories are without supernatural

excess, but he uses light strategically to illuminate

miracles.

Although born in

Pittsburgh, most of his early life was in Philadelphia. He became the

pupil of legendary teacher

Thomas Eakins

in 1879. Although Eakins considered him a star pupil, he faced racial

prejudice from other students. Not receiving recognition in the United

States, he set out for Europe in 1891, and received additional training

at the Academe Julian in Paris. Philadelphia may have been the best place for an American to study art in the 19th century, but Paris was the best place for an artist to be. By 1895, his work was accepted in the

Paris Salon. The next year he received an honorable mention at the

Salon, and in 1897, his recognition was complete with

The Raising of Lazarus, 1896. The success which alluded him the US came after only a few years living in France.

The Raising of Lazarus (top of this blog page, and to the right.) received a third class medal in the Paris Salon, but it also became the first painting to be bought by the nation of France and placed in a national museum. The painting tells the story of Jesus going into the grave of Lazarus to bring him back to life, with sisters Mary and Martha and a group of his stunned followers. Tanner captures in paint the earthly event as it actually could have taken place, but uses heightened light-dark contrast to illuminate the miracle.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Two Disciples at the Tomb, 1906

Art Institute of Chicago, 51 x 41-7/8" |

|

We can think of Tanner as similar to

Caravaggio who introduced dramatic light - dark contrast to show that the calling to follow the Lord is a mysterious event. More importantly, we can think of Tanner like Rembrandt, who used light to convey subtle and mysterious psychological states that accompany a person undergoing a spiritual awakening, or witnessing a miracle. As in the works of both the earlier artists, the drama becomes an interior event.

In 1906, Tanner's painting of

Two Disciples at the Tomb won first prize at the Art Institute of Chicago's 19th exhibition of American painting.. In it, Peter, the older man points to himself as if saying "Oh my God," while the younger apostle John raises is head straining to with expectancy to see fulfillment of Jesus' promise with the Resurrection. Light is strategically placed on the whitened necks against dark clothing, and the glow of their bony faces radiate a sudden awareness of the miraculous event of Christ's Resurrection. They're the faces of simple men, whose faith has saved them.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Three Marys, 1910 Fisk University, Nashville, TN 42" x. 50" |

The Three Marys is a particularly beautiful portrait of women as they see the light in front of Jesus' tomb and that he has risen from the dead. The witnessing of a miracle is a profound spiritual event. Each woman has a slightly different psychological response. Like many of Rembrandt's paintings,

The Three Marys is nearly monochromatic, with blue as the primary color. He explained the intent of his paintings, "My effort has been to not only put the Biblical incident in the original setting, but at the same time give it the human touch....to try to convey to the public the reverence and elevation these subjects impart to me." It seemed that as time went on, the blues get stronger and stronger in his paintings.

|

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893

Hampton University, Hampton, VA | | |

Actually Tanner's best know paintings are

The Banjo Lesson, 1893, at Hampden University and

The Thankful Poor, 1894, in a private collection. He painted them on return to the United States and based them on memories from travel in North Carolina. Instead biblical stories, these paintings are scenes of everyday life. Yet they have a religious significance in their contemplative spirit and the suggestion of humility. The Banjo Lesson has two sources of light, an unseen window and an unseen fireplace or stove to the right. The glow of light shows that he was familiar with Impressionism and applied some of its diffusive, scattered light it.

Tanner traveled extensive to the Middle East and into the Islamic world. Trips to Egypt and Palestine in 1897 and 1898 may have given him inspiration for the settings in his paintings. After 1900, he developed a looser style, with more tonalism and the possibility of becoming more poetic.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, Abraham's Oak, 1905, Smithsonian American Art Museum |

As we may expect, the city of Philadelphia has a substantial collection of his work, particularly where he studied, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The

Smithsonian American Art Museum has a large collection of his works also. I particularly like

Abraham's Oak, which can be read as a pure landscape painting. Also fairly monochromatic, the painting reflects the Tonalist style prevalent in the United States at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Tonalist landscapes are moody, evocative, contemplative and spiritual. He combines the underlying beauty in nature with a symbolic oak, the place Abraham staked out for his people as the Jewish patriarch.

Like the great early 19th century artist Eugene Delacroix, Tanner was fascinated by North African subjects and themes. (I see Delacroix's influence in the vivid colors and the way he treated the floor patterns in

The Annunciation.) He went to Algeria in 1908 and Morocco in 1912. The Atlas Mountains of Morocco are said have been inspiration a late painting,

The Good Shepherd, also in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Figures became smaller, but faith is still his driving force. The unification of subject with landscape has increased. There's a huge precipice these sheep could fall down, but their loving shepherd protects them. According to Jesse Tanner, his son, the artist believed that “God needs us to help fight with him against evil and we need God to guide us.” He lived to be 79, dying in 1937.

|

| Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Good Shepherd, c. 1930 Smithsonian American Art Museum |

(I have seen only one exhibition of his paintings at the Terra Museum of American Art, back around 1996 and the work mesmerized me.) An exhibition in Philadelphia two years ago attempted to bring Tanner the recognition due to him. Here's a professor's

review of the exhibit which also traveled to Cincinnati and to Houston.

There may be reasons apart from racism as to why he is not more famous in America. The United States lacks a tradition of religious painting and doesn't easily embrace it. Furthermore, art historians celebrate artists who are innovators, those who bring art forward. Although Tanner was painting at the time of Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky, Klee and O'Keeffe, he was not strongly affected by their trends of change. He stayed true to himself and in that way, he is a prophet of his faith rather than a prophet of the avant-garde.